What Happens After Retirement

Being a significant life-changing event, retiring from a career as a first responder, can be traumatic. Before retirement, many organizations offer seminars on financial security or about health care and fitness. Very few provide any mental health training. Most will march onward, enjoying a life of retirement; some will not, as there will be emotional and psychological issues. Retirement brings along a great deal of change, and change is uncomfortable, and no one likes to feel uncomfortable.

First Responders tend to internalize their role as a Medic, Firefighter, or Peace Officer. Their identity defines them as a person, and the loss of that identity upon retirement can be devastating. Peace Officers sign retirement papers and give up their Peace Officer powers; they turn in their badges, credentials, and other issued safety gear. Firefighters also must return their turn-outs, their safety equipment, their uniform badge, and identification card. This is when many retirees feel their identities are being stripped away from them. Both are issued new I.D. cards stating they are RETIRED; they are no longer considered “sworn,” and they are shown the front door.

“And when his time of service was ended, he went to his home.”

Luke 1:23 NIV

For many turning in the “gear” and signing the paperwork can be an emotional experience, crying as they say goodbye to their career. Large agencies, such as the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department, assign “handlers,” persons from personnel, to assist with the retirement process. Many will take along a soon to be former coworker to help soften the blow.

Whether they are retiring from a career as a Medic, Fire Fighter, or Peace Officer, they are a member of a unique, close-knit second family; after retirement, it all changes. They no longer feel they are part of the organization, and they no longer enjoy that first responder support. The term “friendly divorce” best describes the situation. When they return to their former second home, they feel like they only have visitation rights.

Most retirees will say they do not miss the job; they miss the people. They may return to the police station or firehouse to visit old friends, only to be treated as an outsider. This separation, the “friendly divorce,” the loss of support from the police or fire family may increase the already heightened physiological and psychological state associated with elements of Post-Traumatic Stress injury up to, and including guilt.

Those exposed to trauma lose their access to that close-knit brotherhood no longer being able to depend on them to reinforce a sense of understanding and recognition of their injury. For most retirees, especially the cops, they remain distrustful and suspicious of others. They become hypervigilant protecting loved ones. There are mood swings causing times of great depression, isolation, and a sense of being lost. Many first responders define themselves by their job. In the 2005 movie “Jarhead,” The character Anthony “Swoff” Swofford says; “A man fires a rifle for many years, and he goes to war. He comes home, and he sees that whatever else he may do with his life like build a house, love a woman, change his son’s diaper, but he will always remain a ‘Jarhead.’”

Those traumatic events don’t just go away; they are memories deeply embedded in the brain. Unresolved, these events can re-emerge, resulting in distressing responses such as depression, anxiety, panic, intrusive thoughts, intrusive images, guilt, anger, grief, and sleep disturbance. These reactions can impact the retiree’s worldview having a significant shock to their general psychological and emotional wellbeing.

This is most significant for first responders who retire with a disability. While others are in some mode of exit, the disabled responder is immediately “thrown” into a new life and one in which they are often ill-prepared to handle.[1] Our responder will spend most of his time fighting with his former agency for benefits to treat his job-related injury. Many leave without any fanfare; they are injured and depressed. A career they worked hard to obtain has been stolen from them; the camaraderie is no longer there; their dreams have been shattered. The tax-free retirement they may receive is a small consolation for the tragedy that occurred.

This is most significant for first responders who retire with a disability. While others are in some mode of exit, the disabled responder is immediately “thrown” into a new life and one in which they are often ill-prepared to handle.[1] Our responder will spend most of his time fighting with his former agency for benefits to treat his job-related injury. Many leave without any fanfare; they are injured and depressed. A career they worked hard to obtain has been stolen from them; the camaraderie is no longer there; their dreams have been shattered. The tax-free retirement they may receive is a small consolation for the tragedy that occurred.

After retirement, first responders no longer have “the job” or their “partners” to distract them from the everyday stressors. They’ve experienced loads of trauma, seen things they cannot talk about to their non-first responder friends; they have feelings that have been “sucked up” for years just waiting to be released. If they have not already done so, many retirees will turn to alcohol or prescription drugs to self-medicate. All of this can lead to heart disease, cancer, divorce, social isolation, and disrupted sleep patterns.

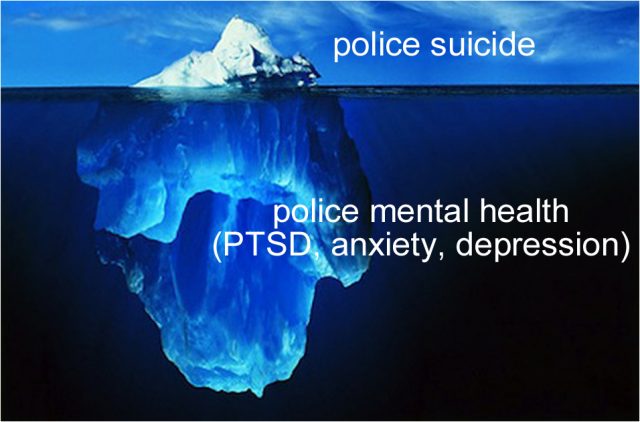

Is Suicide Higher among Active or Retired Peace Officers?

Although retired, peace officers still have to confront and handle the stressors they endured when working. Being unable to erase the horrifying incidents seen in a 30-year career, many officers will dive deep into depression. The “stigma” associated with Law Enforcement continues. The officer will not get help in fear of being ridiculed, in fear of losing that coveted Concealed Carry Weapons permit. As the depression cycle continues, the memories will enhance. Depression plays a significant role in suicides, with roughly 90% of all suicide victims suffering from depression. Severe depression can lead to alcohol and prescription drug abuse, it is well known, among scholars in this field, that alcohol is involved in 30% of all suicides.

Although retired, peace officers still have to confront and handle the stressors they endured when working. Being unable to erase the horrifying incidents seen in a 30-year career, many officers will dive deep into depression. The “stigma” associated with Law Enforcement continues. The officer will not get help in fear of being ridiculed, in fear of losing that coveted Concealed Carry Weapons permit. As the depression cycle continues, the memories will enhance. Depression plays a significant role in suicides, with roughly 90% of all suicide victims suffering from depression. Severe depression can lead to alcohol and prescription drug abuse, it is well known, among scholars in this field, that alcohol is involved in 30% of all suicides.

According to Blue H.E.L.P., an organization that tracks Peace Officer’s suicide, retirees consist of about 13% of Law Enforcement reported suicides. Of course, we know this is low as the status of many people who commit suicide are unknown, and that firefighter and police suicides are under-reported. Between the beginning of 2016 through June 30, 2019, Blue H.E.L.P. documented 578 known law enforcement suicides. Seventy-eight of those suicides were retired officers, of those 78, 25 were retired less than 24 months.[2]

Many assume that the suicide rate among retirees is higher than those still working. However, in a 2011 article in the International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, the authors’ research suggests that the suicide rate generally decreased as years of service increased and as years of separation from police work became more recent. For the years of police service category, the highest suicide rate was among officers with 19 years of service or less.[3]

Thinking, attempting, or completing suicide is not necessarily due to a mental illness. Suicidal thinking and behavior are not “mental weakness;” rather, they are the byproduct of an individual wanting to end extreme (and often temporary) emotional pain. New research in the area of law enforcement suicide has been investigating its relationship to exposure to critical incidents (violence, injury, and death). To be clear, not all law enforcement personnel exposed to a critical incident will experience issues with post-traumatic stress reactions or think about suicide. The important thing is to recognize;[4]

•Exposure to critical incidents – Constant exposure to violence, injury, and death are normal for law enforcement. The higher the number of critical incidents experienced, the more likely mental health symptoms will emerge.

•Untreated/unrecognized mental health symptoms – Slowly over time, symptoms emerge such as numbness, detachment, feelings of hopelessness, and increased substance use. These symptoms are easy to ignore and happen insidiously.

•Personal crisis, performance deficits, and health impairments – If these symptoms go untreated, a personal crisis can emerge such as relationship problems/divorce, work performance issues, and declining health. The ability to cope with the job and personal affairs starts to erode.

•Suicide – Suicidal thoughts can build slowly over time. If left untreated, this can lead to feelings of hopelessness, depression, and anxiety – ultimately increasing the risk of attempting suicide. Anyone can have suicidal thoughts, even people with no prior mental health problems.[5]

6For I am already being poured out like a drink offering, and the time for my departure is near. 7 I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race, I have kept the faith

2 Timothy 4:6-7 NIV

IF YOU HAVE THOUGHTS OF SUICIDE GET HELP NOW

Law Enforcement Copline (800) 267-5463

Firefighters / Medics Fire/EMS HELPLINE (800) 731-FIRE (3473)

“It doesn’t matter who you are, This world gon’ leave some battle scars”

from the song “Scars” written & performed by tobyMac

- Brian A. Kinnaird Ph.D., “Life After Law Enforcement,” Psychology Today, July 15, 2015, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-hero-in-you/201507/life-after-law-enforcement ↑

- Blue H.E.L.P., “Law Enforcement Suicides,” https://bluehelp.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/2016-to-2019-.pdf ↑

- Violanti, John & Gu, Ja & Charles, Luenda & Fekedulegn, Desta & Andrew, Michael & Burchfiel, Cecil. (2011). Is Suicide Higher Among Separated/Retired Police Officers? An Epidemiological Investigation. International journal of emergency mental health. 13. 221-8. ↑

- “Adjusting to Retirement: A Handbook on what to Expect and Resources to Help,” published by the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, Psychological Services Bureau, 2019 ↑

- Ibid, created by LASD Psychological Services Bureau psychologist, Dr. Kim Telesh. ↑

Banner Photo by Yannes Kiefer on Unsplash